Protégé™, Your Personalized AI Assistant

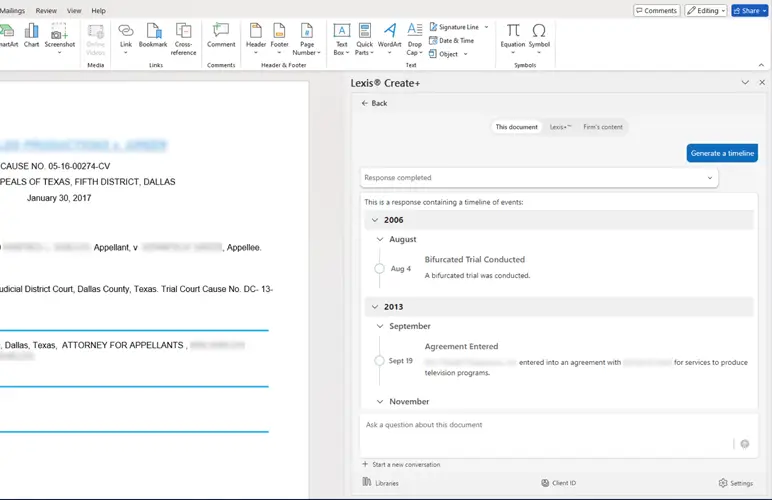

LexisNexis Protégé™ is a personalized AI-powered assistant that enhances productivity and drives next-level work quality for legal and business professionals in the LexisNexis ecosystem. Protégé is currently available in Lexis+ AI® and Lexis® Create+.